Phenomena contextualized in consequential real-world events can help anchor science ideas in meaningful ways for students in science classrooms. In science, we can think of phenomena as things that happen in the natural world (Windschitl et al., 2018). When students see a purpose for explaining something that happens that’s impactful or relevant to them, they are motivated to figure out how science works and what it can help do for the world instead of just learning about science topics (NGSS, 2016).

Centering justice in classrooms means reconsidering the anchoring phenomenon for the unit. What social, environmental, cultural, and political components are connected to the events? What and who is traditionally left out in the telling of this story in K-12 classrooms? Who does this ultimately serve? The dimensions below highlight at least four dimensions of justice that we consider for K-12 science units; not including these dimensions upholds White dominant ways of thinking and will ultimately reproduce inequities.

- Nature-Culture Relations & Ecological Caring

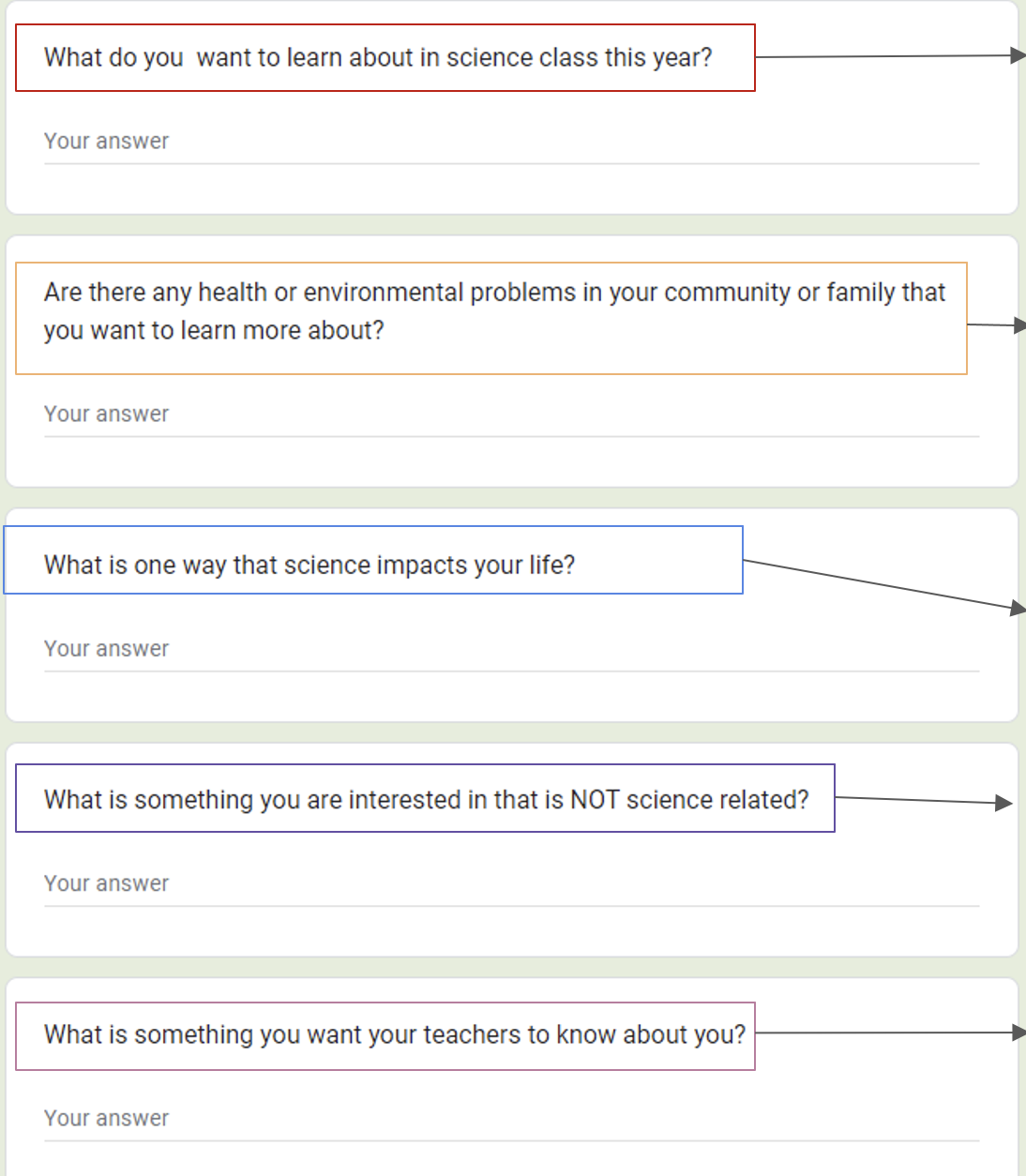

Too often in classrooms, science is presented as equations and facts separate from human lives and culture. Nature is a part of human existence, and vice versa. Consequential, real-world phenomena show the interconnected relationships among place, nature, and culture. (Bang & Marin 2015; Learning in Places Collaborative. 2020) - Culture, Families, & Communities as Rightfully Belonging

Who belongs in a science learning environment? This question may bring to mind ideas about inclusion and representation, like including contributions from diverse scientists in a classroom. The idea of “Rightful Belonging” extends beyond these notions. All stakeholders have the right and the responsibility to re-author and transform what it means to participate in science learning and to bring their whole lives to bear. (Calabrese Barton & Tan, 2021; Tan & Barton, 2021) - Broadening Languages of Science

Multilingual students’ ways of communicating provide value and points of leverage to expand science discourses and sensemaking. Science educators must recognize the linguistic value of all of their students and the communities they come from. Diversity in language reflects diversity in thinking and opens the door for deeper learning. (Suarez, NGS Navigators, 2019; Suarez, 2019) - Power, Histories, & Futures Matter

Science is a profoundly cultural endeavor, and human experience has been entwined in helpful and harmful ways with discoveries and their applications. For instance, power within society and power within a classroom both determine which ideas get taken up and how ideas get used. Histories of peoples and places continue to shape the experiences of students and their communities. And keen attention must be paid to the possible futures of students and how their engagement with and use of science might shape those outcomes. (Giroux, 1994; Gomez, 2021; Tauheed & Jones, 2022; Thomas, 2021; Winn, 2021, 2022)

This site is primarily funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) through Award #1907471 and #1315995

This site is primarily funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) through Award #1907471 and #1315995