Providing a blank page for students to create their models can make some students freeze up when asked to explain how/why a phenomenon happens. However, too much scaffolding can make students feel like there is one specific “answer,” limiting idea generation. Here are six tips to help find balance.

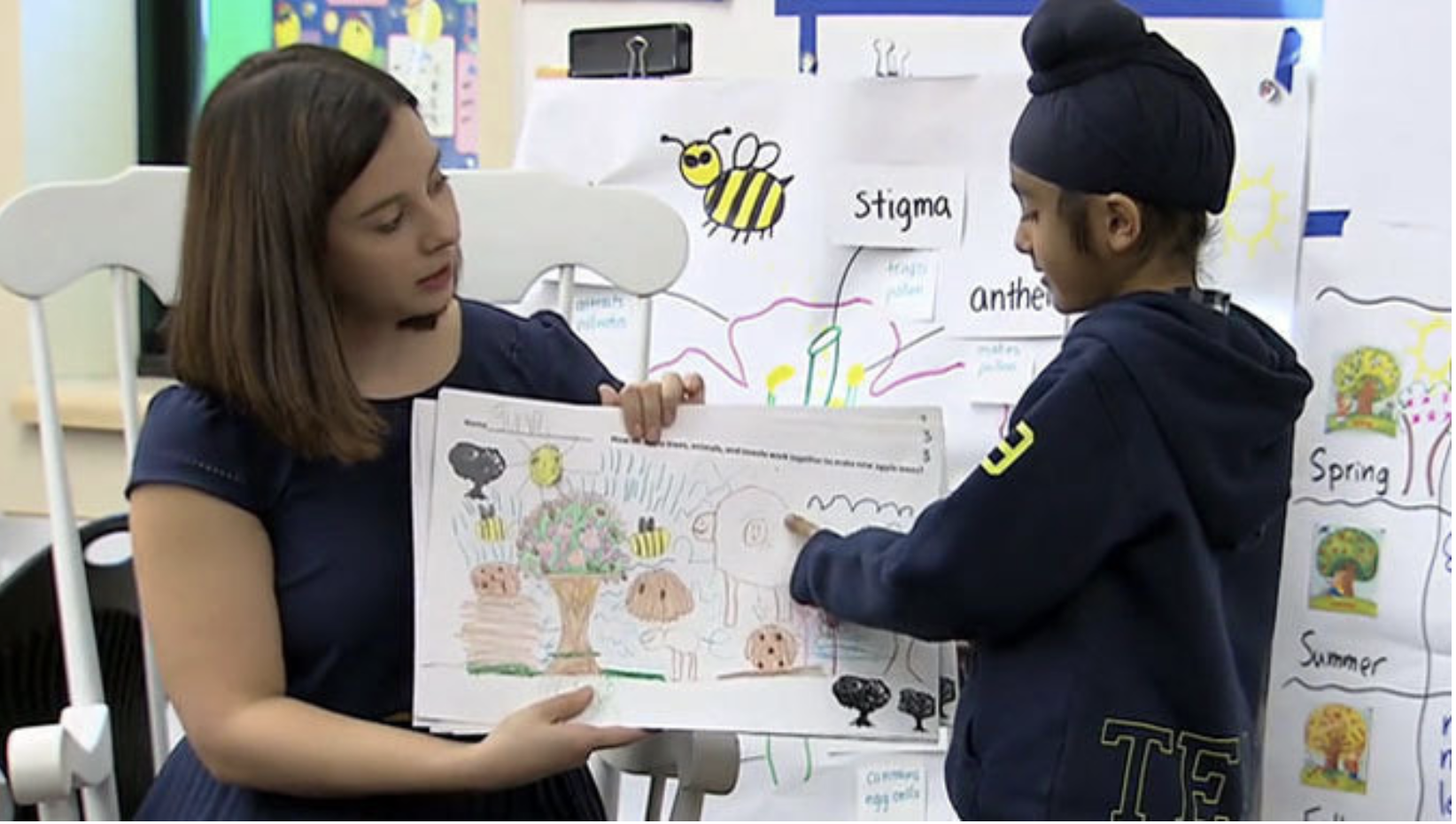

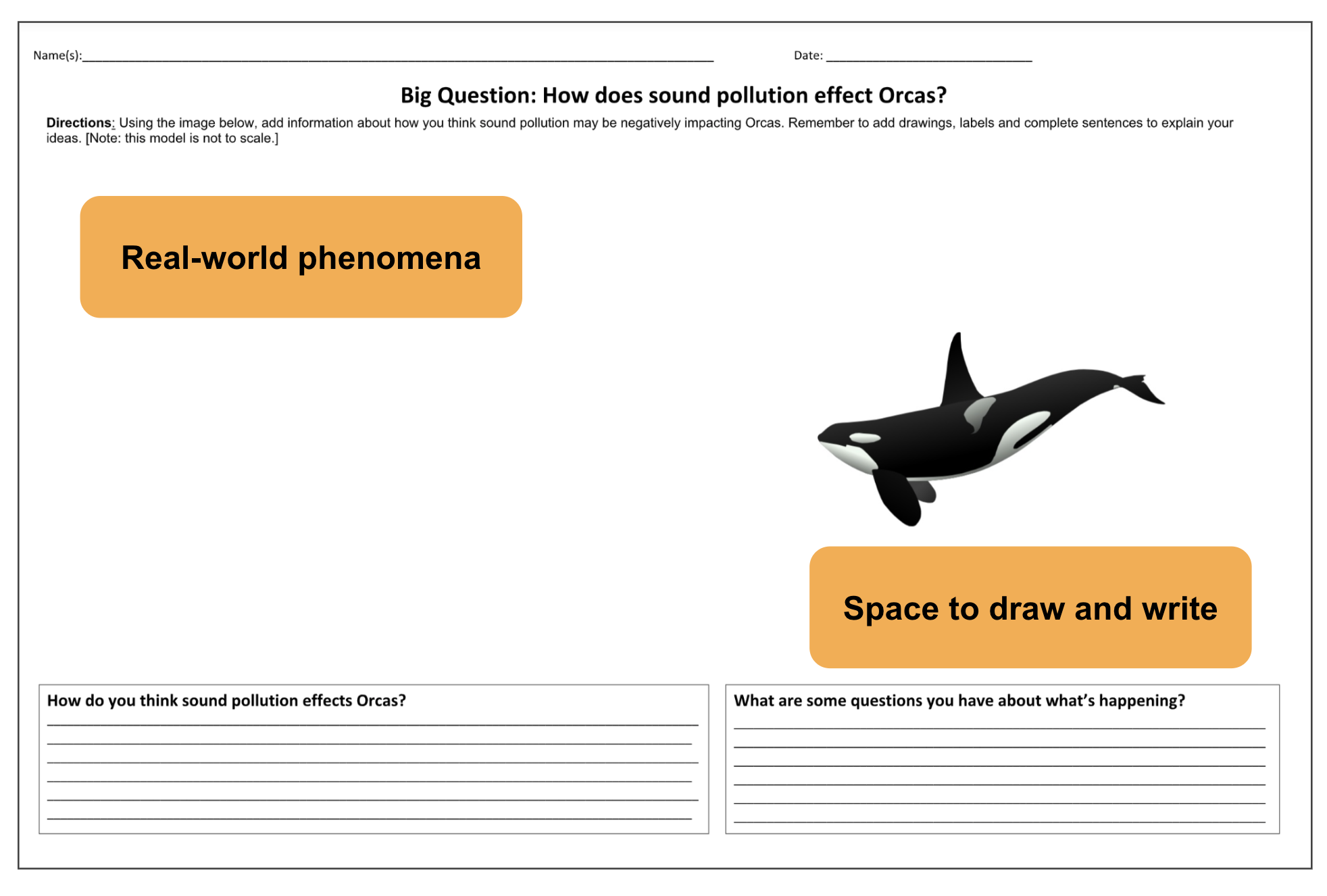

1. Connect explicitly to an observable event. Include a specific question about the unit event or phenomenon that students must explain or figure out. This is an event students can observe, watch, or replicate to make their own observations. This should be an event within a specific context – not a generic process like the “ecosystems.”

2. Structure spaces for drawing and writing. For instance, lines indicate to students that you want them to write. Adding features like “zoom-ins” within a drawing space can prompt students to show what they think is happening that they can’t see. Also, drawing spaces are usually not entirely blank. Starting a drawing for students using observable items gives students a frame of reference and prevents them from “overdrawing” the perfect ocean, whale, etc. Small components like these can help students focus more time and energy on getting their ideas on paper.

Providing ample space for drawing and writing is helpful in cultivating creativity and supporting sensemaking. Most copiers can accommodate ledger size (11”x17”) paper, which is the same size as two letters (8.5”x11”) sheets next to each other. Blog post: Modeling Support: Scaffolding versus White Space

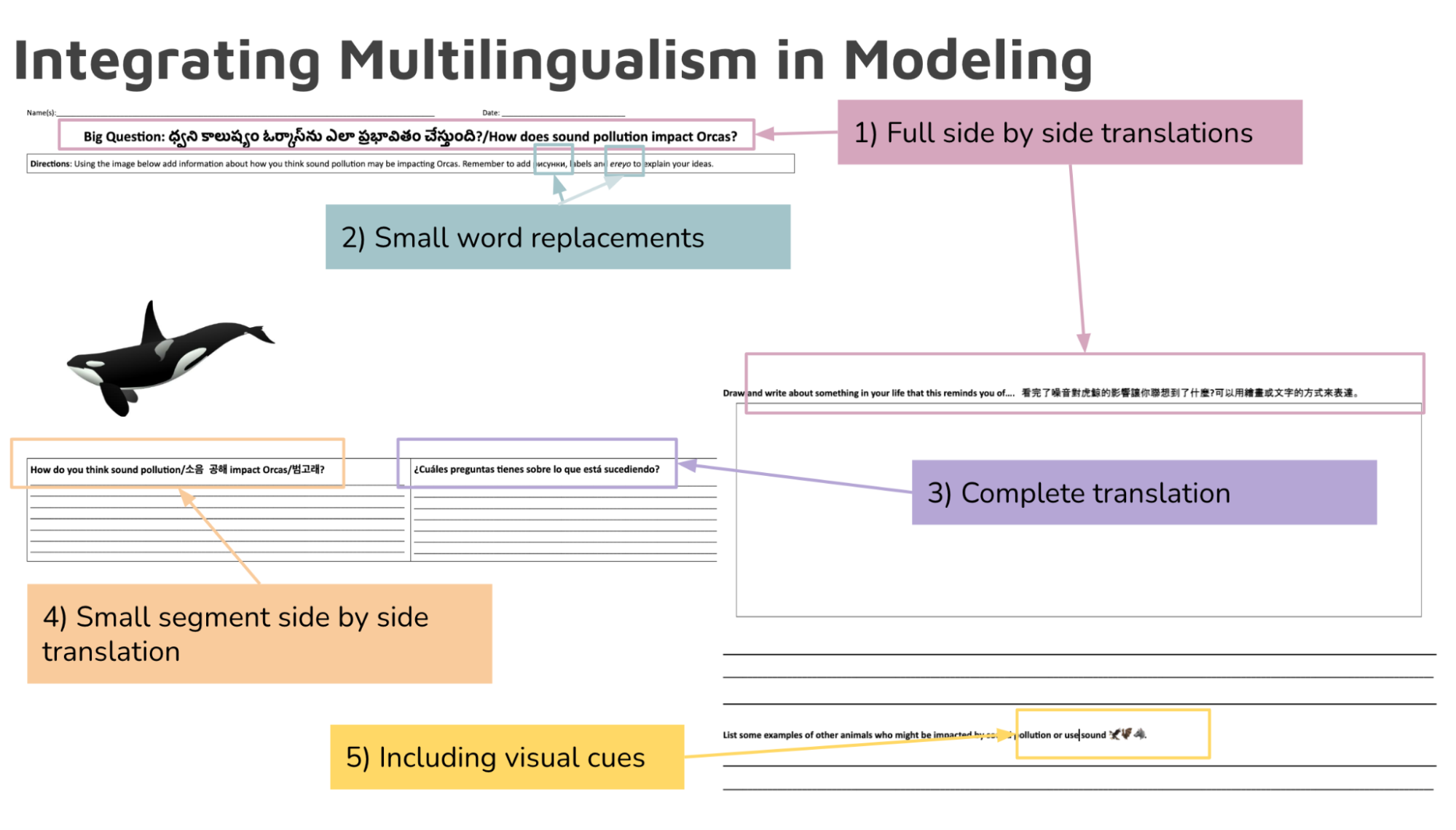

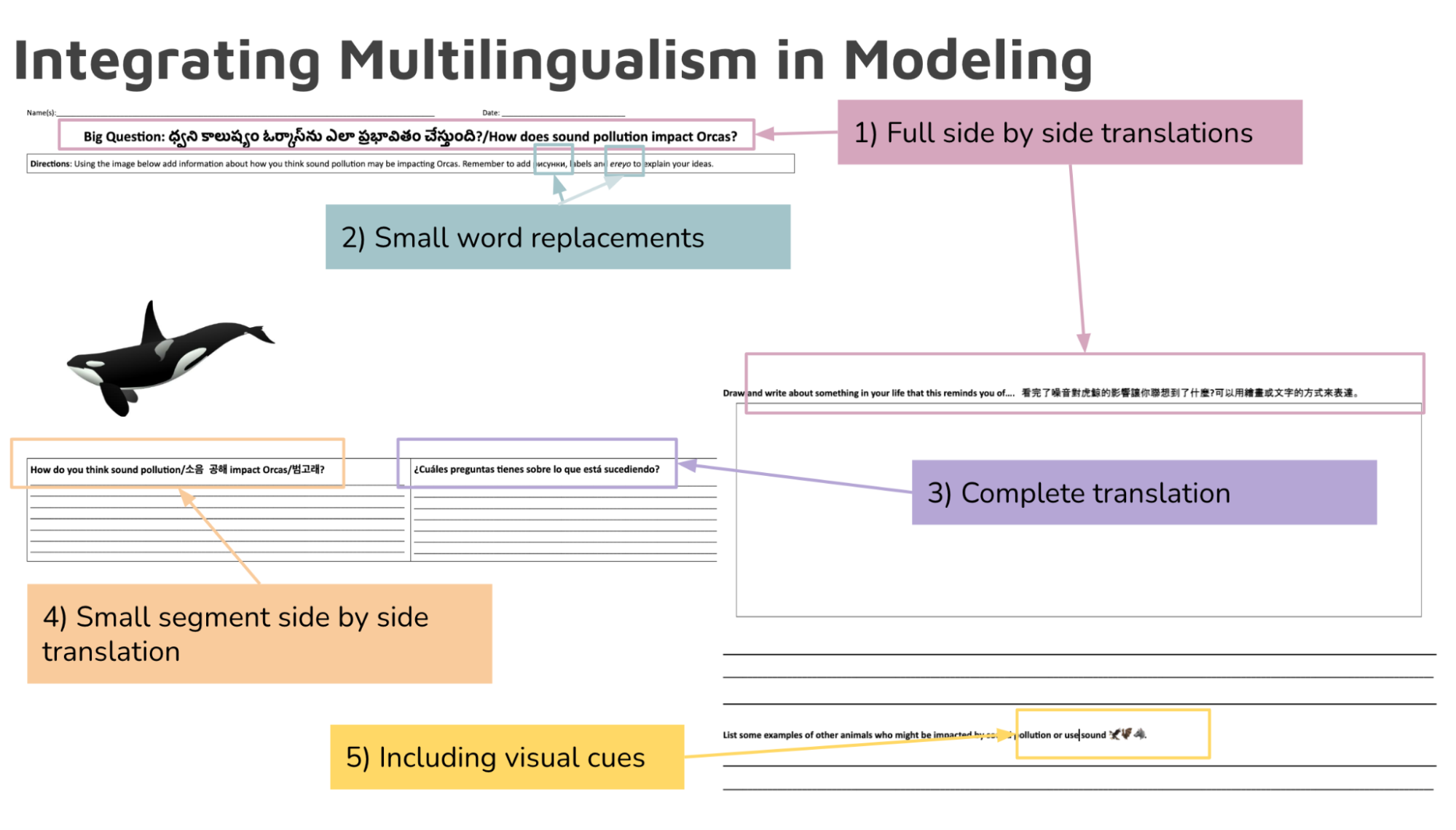

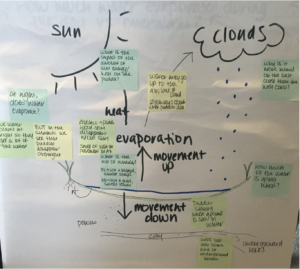

3. Include multilingual prompts. Since model scaffolds elicit students’ ideas, students should have explicit opportunities to draw on their cultural and linguistic backgrounds. This will enrich the conversations about scientific ideas for all students. Here are some techniques for using multilingualism in models (see image).

The placement of students’ home languages on the page sends a subtle message about the importance of their multiple linguistic resources. For example, if you always place English first, followed by Spanish, or if you always include English in regular font with Portuguese in italics, that sends a subtle message to students that their home languages are not as valuable as English. Vary how you include multilingual prompts. You might sometimes print home languages other than English first, followed by English.

In the model directions, explicitly welcome students to use all of their language resources to complete their model and respond to prompts. Without this explicit instruction, students in English-medium science classrooms might appreciate the multilingual prompts but not feel comfortable responding in languages other than English. For example, your directions might state: “Puede utilizar todos sus recursos lingüísticos mientras completa sus dibujos, agrega etiquetas y explica sus ideas. / You may use all of your language resources as you complete your drawings, add labels, and explain your ideas.”

If you are feeling uncertain about how to translate model scaffolds into the various home languages represented in your classroom, here are some tips: 1) reach out to the family/community liaison or multilingual support staff at your school or in your district to ask about available translation services; 2) use free online translation tools, such as Google Translate; 3) ask parents and students to proof-read and suggest corrections to your model scaffold translations.

Consider discussing with your students why you include multilingual prompts. How do multilingual prompts align with your stances about who can do science and what ideas are worth sharing? In what ways can multilingual prompts decenter English as the only acceptable language for science sensemaking in classrooms?

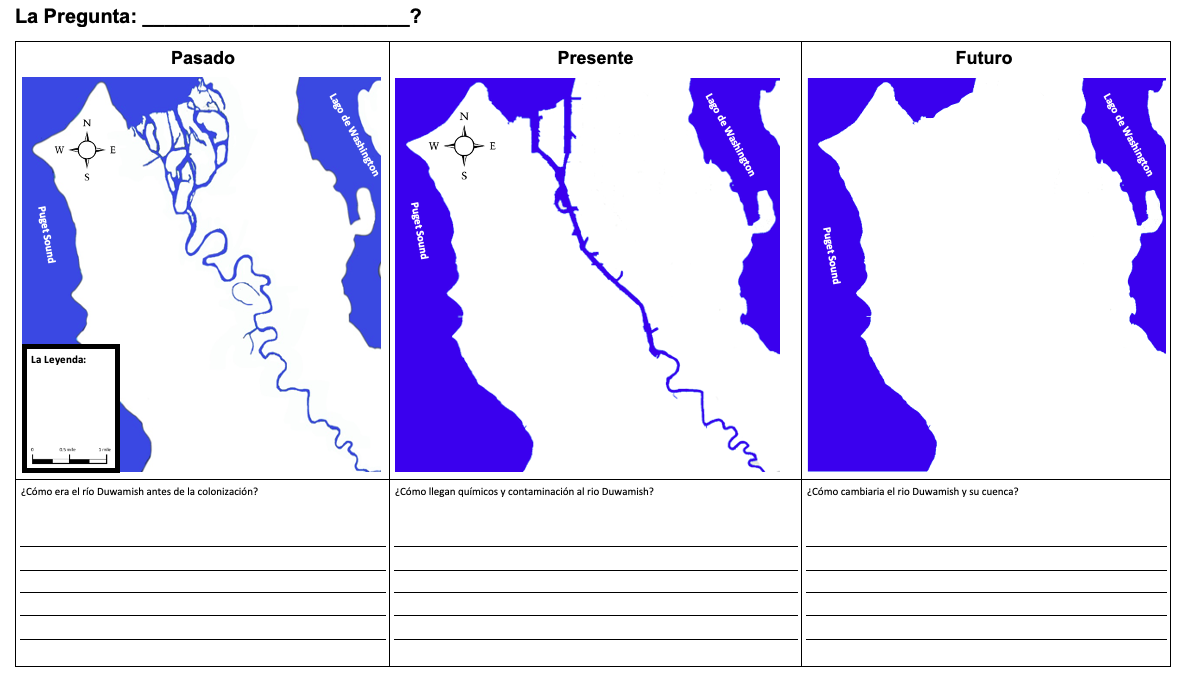

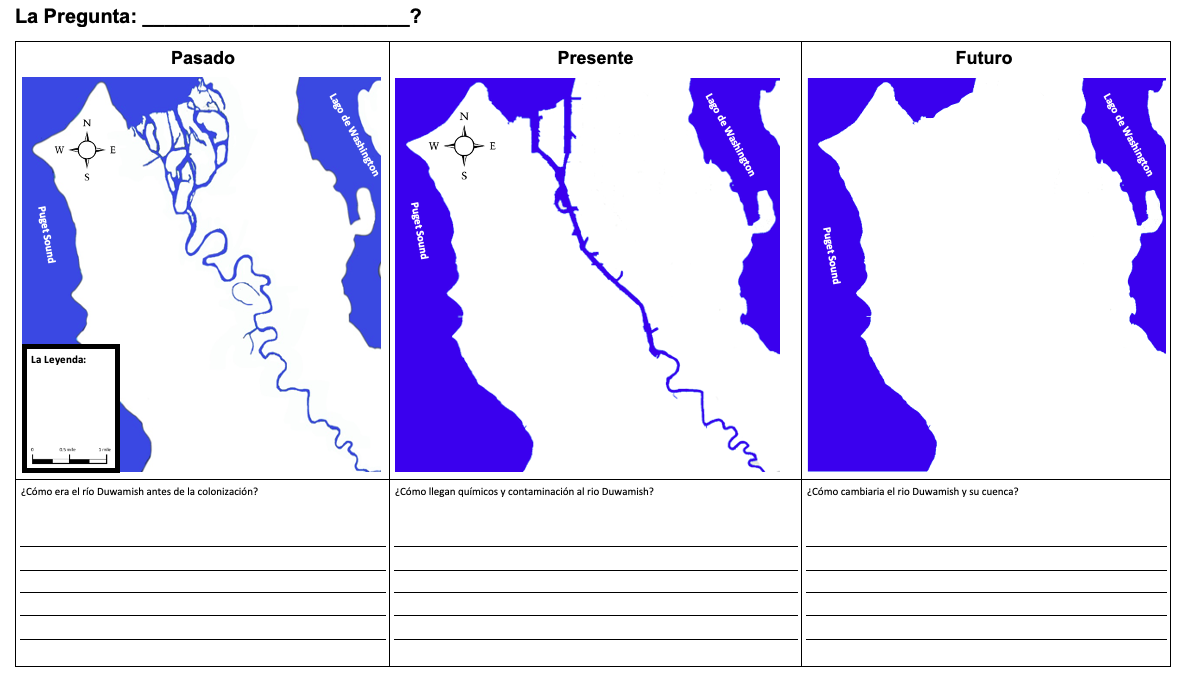

4. Show changes over time. Showing changes over time helps students understand the history of phenomena and connections to larger social, cultural, and political dimensions within communities. For instance, the model below is divided into frames of the past, present, and future landscape of the dxʷdəwʔabš (Duwamish) River. (Other versions have included a before/during/after model scaffold.) This scaffold allows students to reason about the consequences of an event and possible futures. In the case of the Duwamish River, it was declared a superfund site in 2001 due to industrialization. Restoration efforts for salmon are underway. Students can draw the river in the future panel and discuss how the river would change.

5. Consider including prompts on the back. If space is tight on the front of a model scaffold, consider including prompts on the back. For instance, a simple prompt of, “This reminds me of…” allows students to share their expertise and prior experiences and elevate connections they think are important. The teacher and class can then use these ideas to support and extend sensemaking. Here are some kinds of prompts you may consider including:

- Prompts that uncover personal connections: When students can relate to the phenomena emotionally and intellectually, they are more invested and interested.

- Prompts that invite questions: Students’ wonderings can be an important resource for driving personal and class sensemaking.

- Prompts that encourage consideration of impact: Students can identify connections and use learnings to take action in the world (i.e., building sustainable gardens (K unit)).

- Prompts that encourage storytelling: Students may use varied narrative forms to tell stories connected to their lives.

6. Over time, engage students in more decision-making with model scaffolds. As students become more comfortable and knowledgeable about engaging in modeling, they can take on more decision-making. One way to release decisions to students is to provide a model scaffold “buffet.” This is a line-up of pieces of model scaffolds that students can choose to take and use and may include: a checklist of things to consider including in this model; small zoom-in shapes that students position where they want them; pre-drawn parts of the system, especially detailed or complicated ones; etc. The buffet could also have multiple model scaffold options, including blank pages. Students can take any parts and pages they think would be helpful to them to represent their thinking.

This site is primarily funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) through Award #1907471 and #1315995

This site is primarily funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) through Award #1907471 and #1315995