Tip 1: Keep claims specific. Sentence starters that help students identify, discuss, and write claims should be specific to the learning goals for the activity and phenomenon the class is studying.

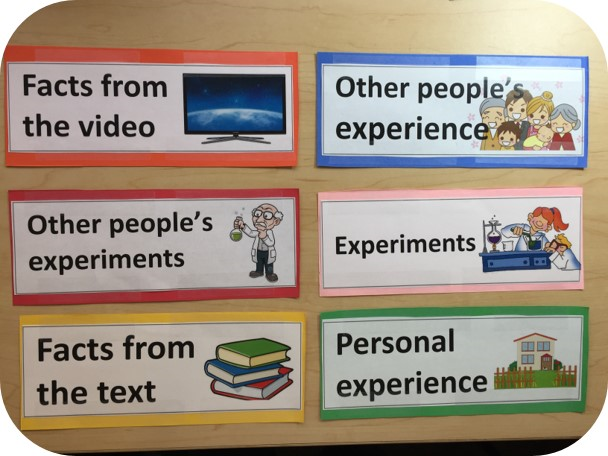

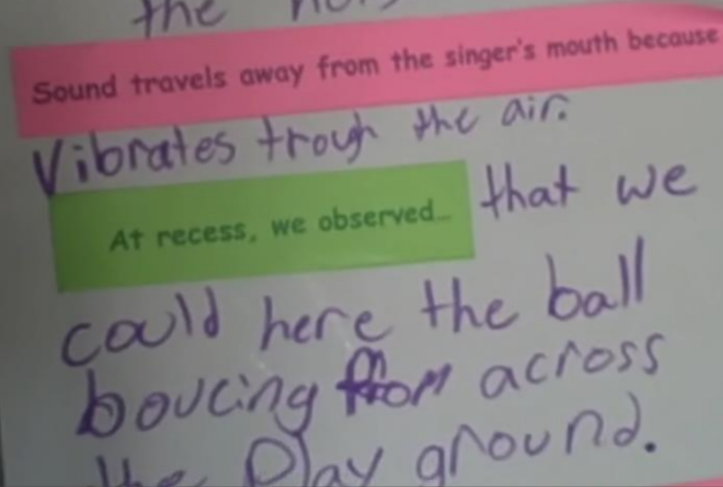

Tip 2: Consider varied forms of evidence. Evidence sentence starters can point students towards varied experiences they’ve had. These experiences might involve data from an experiment or a text source, or they may be relevant experiences a student has had outside of class. Starters might sound like: “We read that…”, “During recess, we observed…”, or “I know this from…”

Tip 3: General connecting phrases can support reasoning. Reasoning sentence starters should be the most general and open. This should allow the widest range of student ideas to come forward. The goal is to help students connect evidence to their claims, so connecting phrases are helpful: “This evidence shows…” or “This result can be explained by…”

Tip 3: General connecting phrases can support reasoning. Reasoning sentence starters should be the most general and open. This should allow the widest range of student ideas to come forward. The goal is to help students connect evidence to their claims, so connecting phrases are helpful: “This evidence shows…” or “This result can be explained by…”

Tip 4: Practice with and personalize sentence starters. As with any classroom tool, it is important to practice with sentence starters and develop norms for how students may use them. For instance, if students feel confused or confined by the phrasing of some sentence starters, they can rewrite them or decide not to use them. Here are a few other ideas for practicing:

- Printing out available sentence starters, color coded by kind (Claim, Evidence, or Reasoning), can let students choose starters that feel most natural to them and move them around to construct arguments. For instance, an early use might invite students to select and sequence multiple claims to tell the science story they want to tell from an investigation, then add in evidence and reasoning pieces.

- It can be helpful to have students work in pairs or groups on a single document or poster. Students can discuss with each other using language that is natural to them before formalizing their ideas into an argument.

Tip 5: Remind students to use available resources. If you have developed a summary chart or a driving question board, these might provide students with clues as to what can be included in their argument. Students can refer to such artifacts and remind themselves what evidence they have collected.

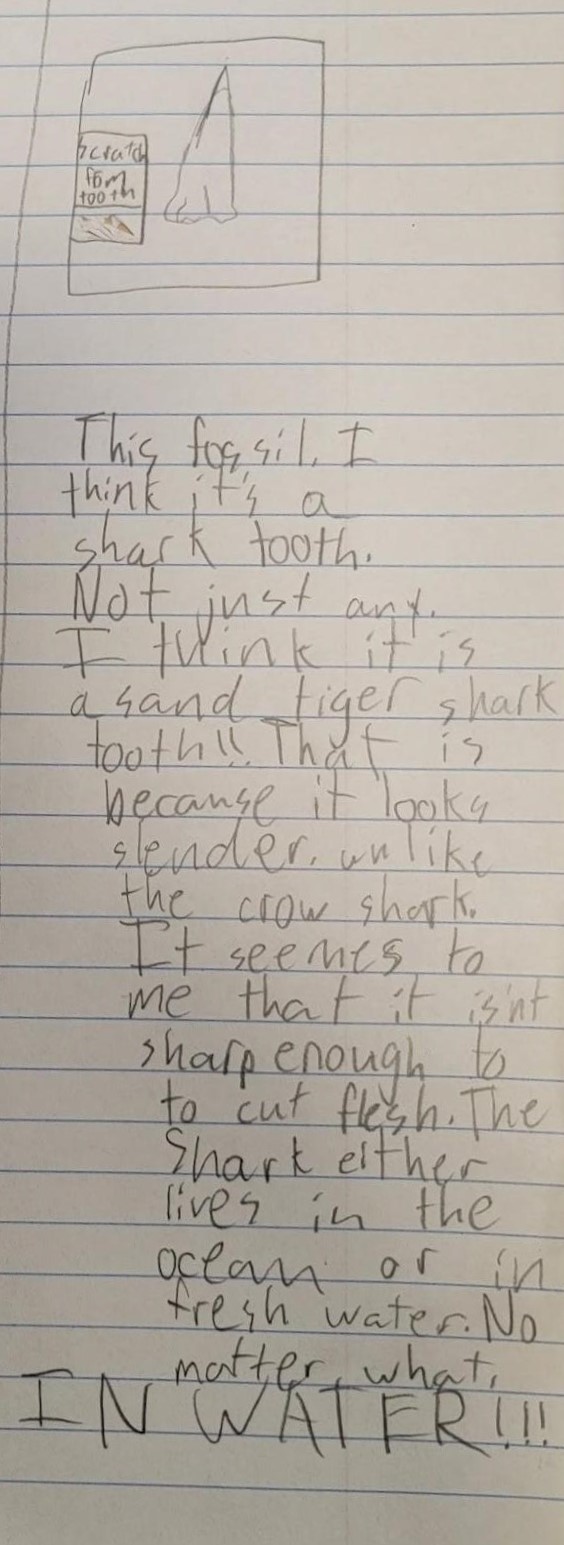

![“I think this fossil is a crinoid because its not [curved around] instead its straight like crinoid. It likely lived in the ocean, because I [experiment?] that is a crinoid and crinoid lives in the ocean. I know this because I used evidence I know and from the info sheet.”](https://ambitiousscienceteaching.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/image4.jpg)

This site is primarily funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) through Award #1907471 and #1315995

This site is primarily funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) through Award #1907471 and #1315995