Design Considerations

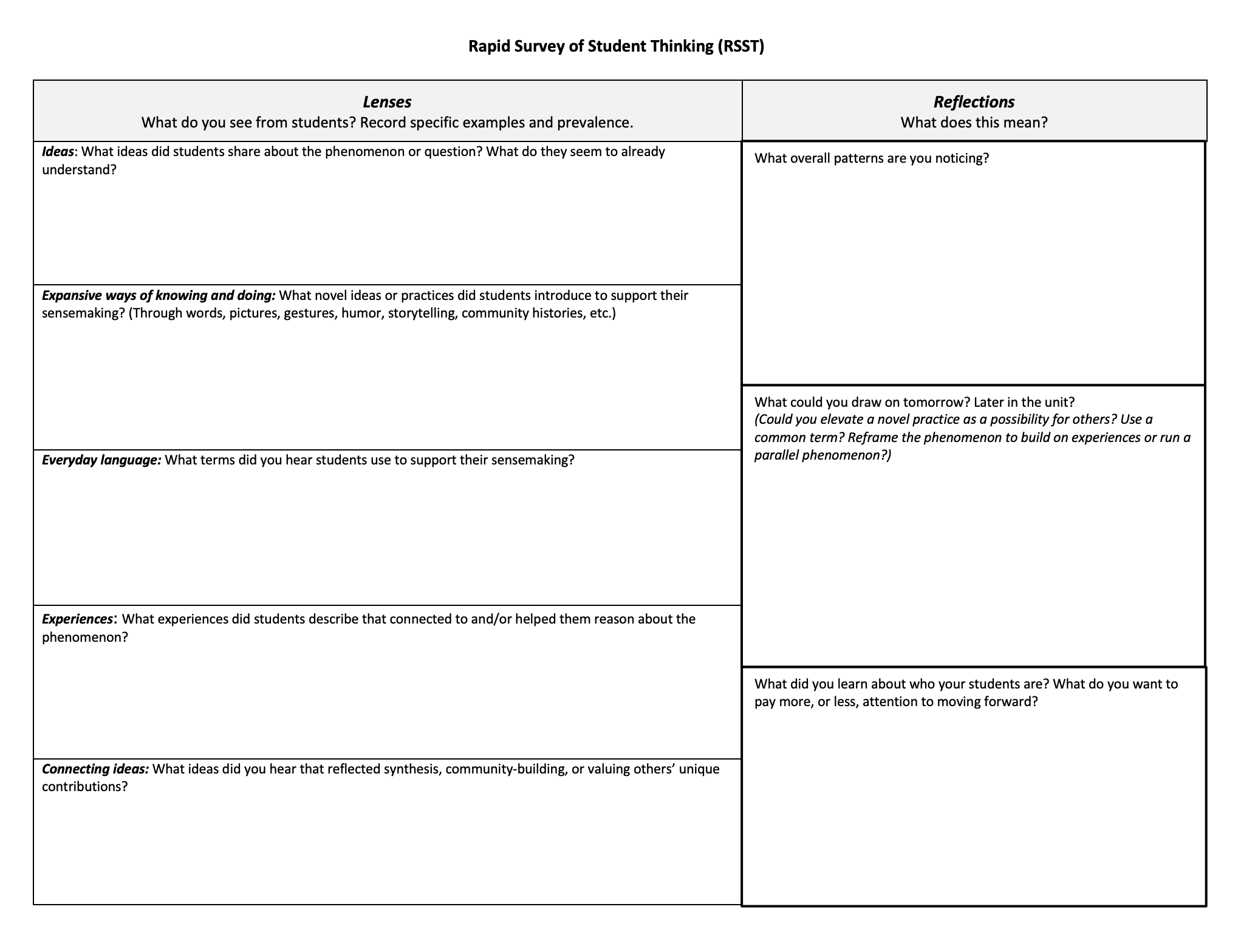

Teacher educators have used the RSST for different purposes and as part of learning opportunities in TE courses or PL.

Purposes: The RSST has been used with pre- and in-service teachers to…

- Help teachers learn to elicit and listen to student resources

- Broaden the lenses we use in making sense of student contributions

- Inform planning decisions

- Learn more about students, their communities, and connections they make to science

- Develop common language in teacher teams

You may want to use the RSST as part of the following kinds of teacher learning opportunities:

- Video analysis: The RSST could be used to make sense of student thinking and interactions in a classroom video. In a methods course, for example, teacher candidates could be split into small groups who each try on one lens when watching, then engage in a jigsaw or whole-group discussion to think across lenses.

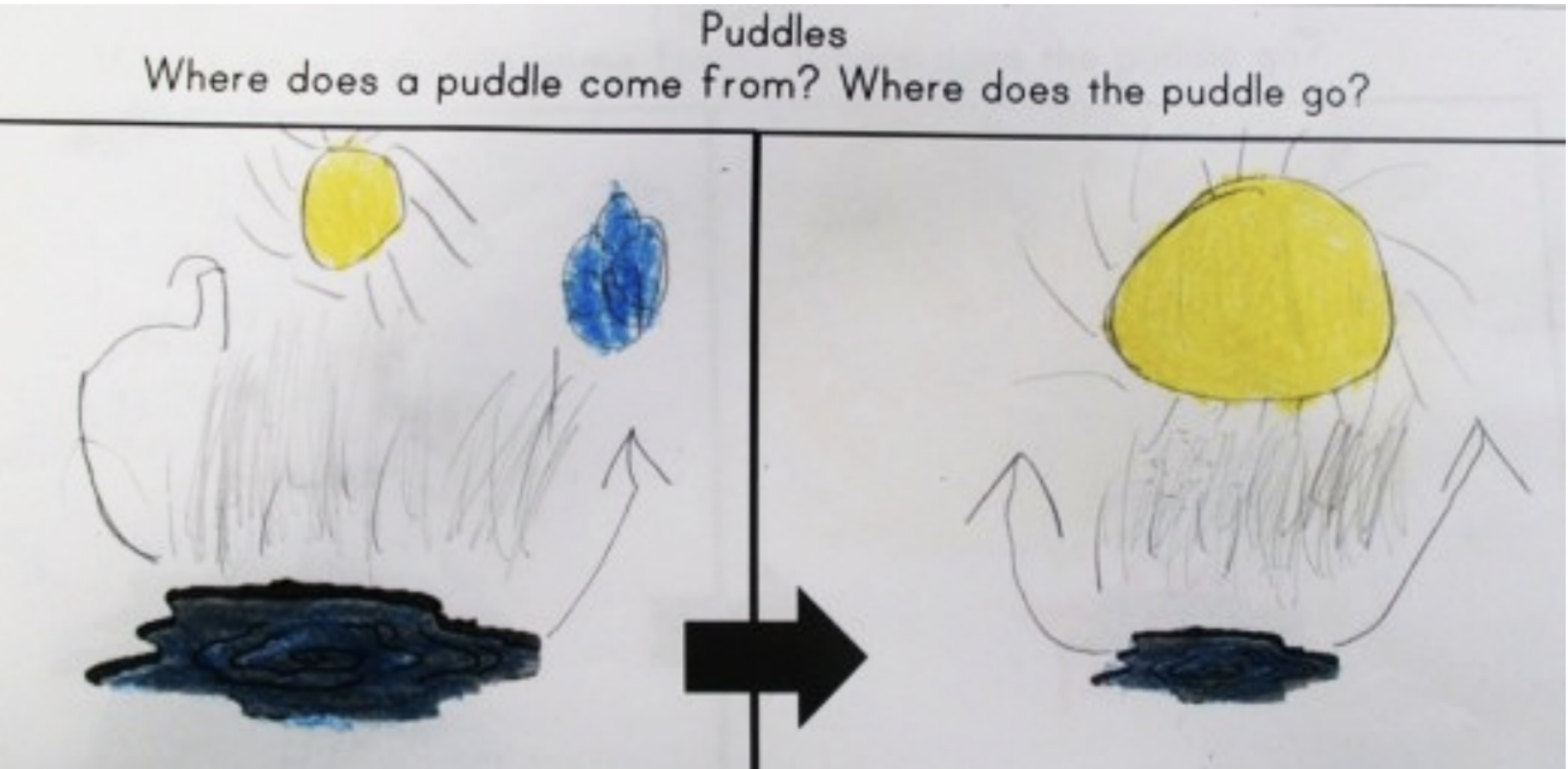

- Student thinking interviews: Several methods courses ask teacher candidates to interview a student or small group of students about a phenomenon and how/why it happens. The RSST can be helpful for anticipating what students might offer and analyzing what students do contribute.

- Reflecting on instruction and/or student work: The RSST can also function as a tool for reflection. For instance, if you fill out the RSST after a lesson and one or more lenses are blank, what might that mean? Are there implications for lesson design, classroom power dynamics, etc.?

- Planning for instruction: Lesson design can also benefit from the RSST up front, as it can prompt questions you might ask students.

In our experience, the “Expansive ways of knowing and doing” lens requires the most practice and support. We must continue learning about varied, rich sensemaking repertoires not often reflected in the Western, white, middle-class practices privileged in school science. With teachers, exploring the worked vignettes in the “Toward Equitable Learning in Science” chapter is one way to get started.

Videos

Videos to practice with the RSST tool in PL or TE

These are videos we have used to couple with the RSST tool in PL and TE methods courses.

Here is an asynchronous professional development that includes the RSST tool. Critical Approaches to Discourse is designed for teachers to use in partnership with others to consider critical equity approaches to analyzing and reflecting on classroom discourse. This module pairs with this video in which a 2nd-grade teacher uses the KLEWS chart around the key concept “landforms are made of rock.” During this lesson, a student asks, “Are all landforms made of rock?” A conversation unfolds between the teacher and the students. As you watch the video (from 6:38-9:50), please think of the following questions.

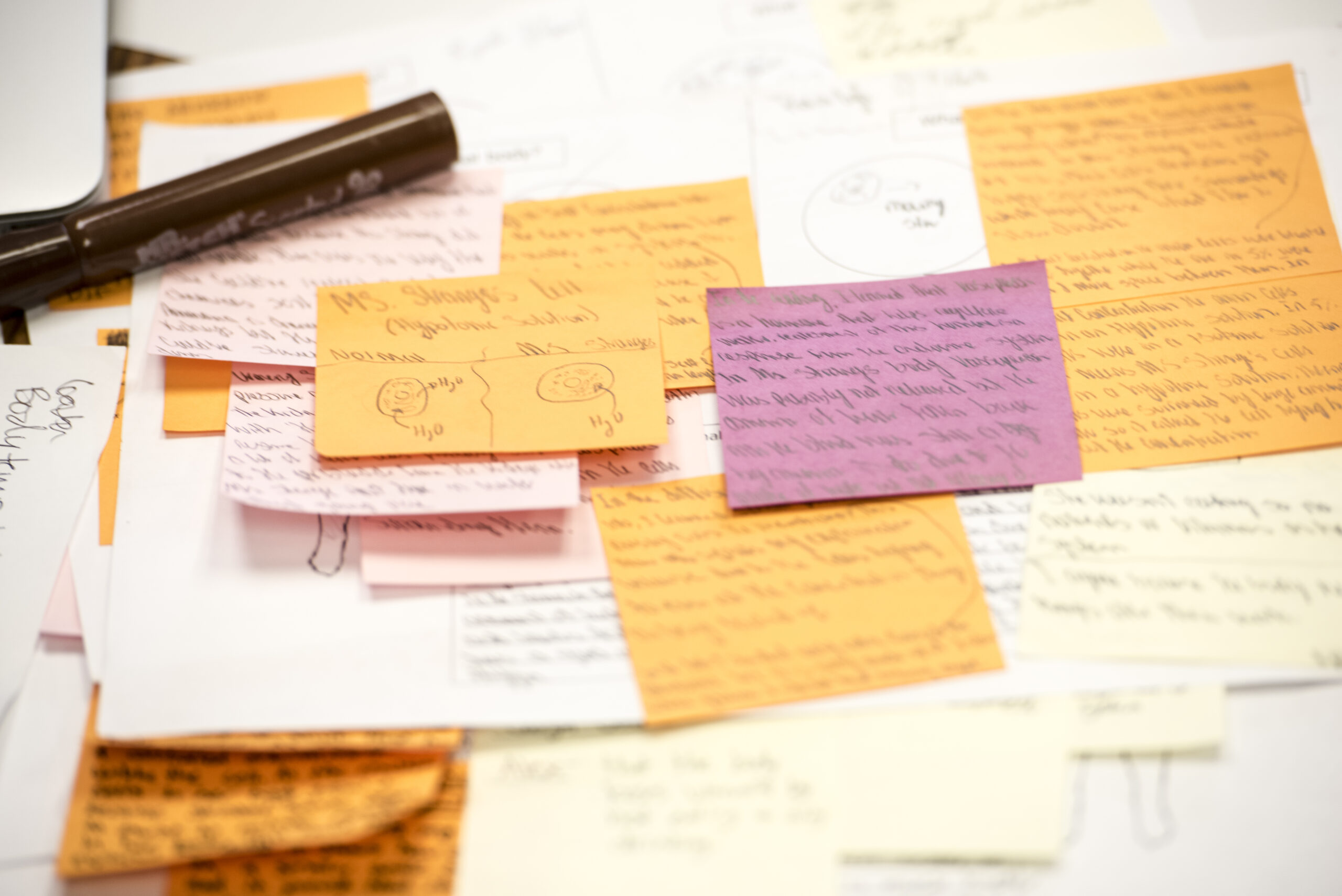

Here is an example of teachers debriefing student work during a job-embedded professional learning activity during a studio day Debriefing (PL video).

Stories

Preservice Teacher Learning about Students’ Initial Thinking and Their Own Questioning. The RSST was a generative tool for a preservice teacher’s parsing of student thinking for an interview-based assignment in a secondary science methods course. The preservice teacher interviewed high school students about a video of a controlled burn on a field of dry grass, inviting students’ noticings and initial explanations of what was happening to the grass microscopically as it burned. Using the RSST attuned the preservice teacher to diverse resources like lived experiences (such as a parent’s work at a nearby fire department) and students’ varied uses of similes and related scenarios to reason. The preservice teacher also reflected on the implications for their instructional planning and what they learned about themselves as a questioner. This included acknowledging the effectiveness of asking students to say more about “jumps” they seemed to make in their reasoning. (Dr. Heather Johnson, Vanderbilt)

Identifying Student Resources in Secondary Methods Courses. Two teacher educators use the RSST in their secondary preservice methods courses to help teacher candidates learn the importance of making student ideas visible as they engage in sensemaking about real-world phenomena. It is often surprising to preservice teachers how difficult it can be to uncover students’ ideas and avoid leading students to “correct” science explanations. To practice this skill, preservice teachers conduct clinical interviews by posing a question about a phenomenon with the goal of bringing student ideas to the surface. For example, one preservice teacher asked their students, “What do you think is responsible for cancer?” During the ten-minute interview, he used AST teacher talk moves (e.g., probing and pressing questions) to facilitate a discussion of students’ ideas. In describing how cancer spread, one student responded that the cell became “pregnant” and “pushed out” the babies. Using the RSST, the preservice teacher noted the student was thinking more expansively about what they knew about human reproduction and trying to map that onto how cells might reproduce. It turned out that this idea was a fairly common idea with his students that he had not anticipated. By using talk moves and making space for students to work through their reasoning, the preservice teacher was able to identify many different ways students tapped into their sensemaking repertoires. The preservice teacher was then able to use this expansive way of knowing as a valuable resource to incorporate into his planning for his unit on cell division. (Drs. Heather Johnson & Kirsten Mawyer, Vanderbilt and University of Hawai’i)

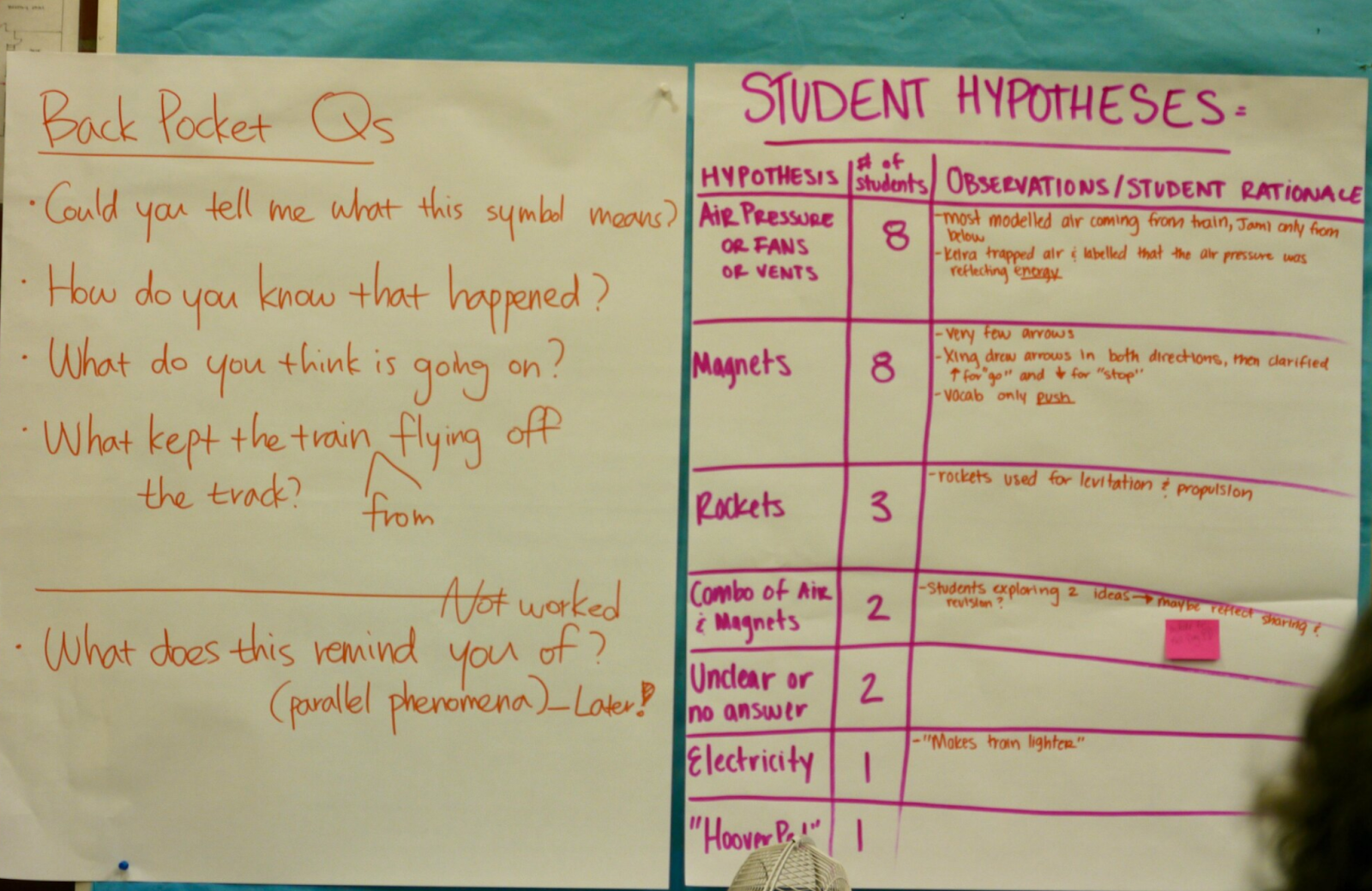

Job-embedded Professional Learning & Students’ Hypotheses. As a part of orienting to NGSS and a new curriculum with a local school district, 30 teacher leaders ran a summer program at a community center. After eliciting students’ ideas about how a maglev train worked and students’ experiences with trains in Seattle, we recorded a list of hypotheses students suggested for how and why the maglev train worked. Interestingly, many students considered how air pressure might be involved. Since the curriculum did not address ideas related to air pressure, we added lessons with hair dryers to help students reason with this hypothesis. Teachers walked away understanding that examining ideas not as right or wrong, but rather as multiple hypotheses, helped deepen students’ ideas of forces and motion. (Dr. Jessica Thompson, University of Washington)

This site is primarily funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) through Award #1907471 and #1315995

This site is primarily funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) through Award #1907471 and #1315995