We have two teacher education series on this website. This one models a full unit aimed at sophomore biology, the other is a middle school unit on physical science. Both of these units demonstrate our “apprenticeship” system for getting our new teachers to take up Ambitious Science Teaching. In this unit, taught in a methods class, our novice teachers actually co-teach with me. Their peers take turns acting as “students.” It works remarkably well, in part because the novices have had a previous methods class with me in which I modeled the four core sets of practices. In this previous unit they experience what it is like to be a student, engaged in ambitious learning.

What you see in these videos is certainly not all that goes on in the methods class. We have discussions about many aspects of teaching, equity, assessment, classroom management, etc., that do not appear in this series. And, the methods instructor cannot be the only one in the system advocating for ambitious teaching. The vision has to be shared by others in the teacher education program and the cooperating teacher, with whom the novices will test out their skills in real classrooms.

Below you can watch the introduction to our approach in working with aspiring educators.

Planning for engagement with big science ideas

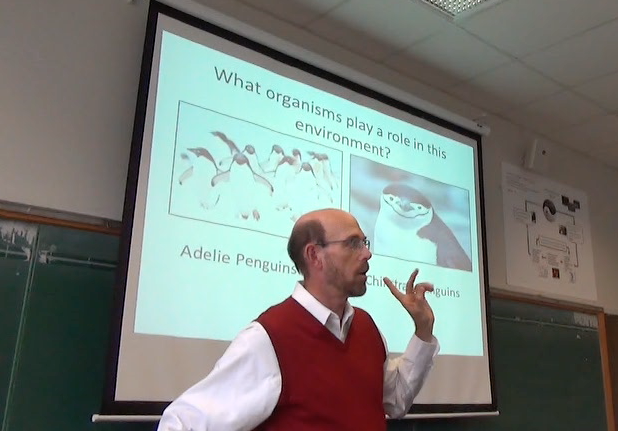

As a group, the novice teachers and I work through the core planning practices. We are playing the role of high school biology teachers who are designing units on ecosystem dynamics. We look through the standards and our curricula, then identify an anchoring phenomenon. In this case it is the puzzling decline of Adelie Penguins in the Antarctic. Even scientists are not sure what is involved in this downward trend, and that makes it an authentic problem for our students. Following that we develop an explanation and a sequence of activities matched to that explanation. There are some routines and tools shown here that you’ll find useful.

Eliciting students’ ideas: Part 1

Four of my novices co-teach with me as we initiate the core practice of eliciting students’ ideas. The anchoring phenomenon has to do with the decline of the Adelie penguins and how climate change might play a role.

Eliciting students’ ideas: Part 2

We finish the practice of eliciting by creating two types of representations of students’ initial thinking. One is a small group model, collaboratively constructed by clusters of students, and the other is a list of possible hypotheses for the decline of the penguins. One nice thing about watching video shot in a teacher education setting is this—as the instructor, I can show more strategies than a teacher might use in his/her classroom. So the novices see a range of what’s possible for this core practice.

Debriefing everyone's initial models

We look across all the models we’ve created and start to see ideas that some groups have incorporated ideas we should all think about further. This is a way of making reasoning visible, to acknowledge that everyone has the seeds of a good model, and to stress that these models should change as we learn more. One of my novices volunteers to act as the teacher and lead the debriefing.

Round 1 of supporting on-going changes in students’ thinking

We use one of the core practices in the set called “Supporting on-going changes in student thinking.” This is a hands-on data collection activity using beans to represent energy that gets passed along different trophic levels in the Antarctic. We show a bit of direct instruction that precedes this, and of course we emphasize the sense-making talk that happens during and after this activity. The end of the video is a good example of sense-making talk that is generated by one of the novices, acting as the teacher. He uses a Summary Table to help him guide this whole class conversation. Many of our novices are apprehensive about whole class sense-making conversations. But having specific goals in mind, a tool like the Summary Table, and a repertoire of discourse moves is super helpful.

Revising our list of hypotheses

We use one of the core practices in the set called “Supporting on-going changes in student thinking.” This is where we revise one of our public representations of thinking—the list of hypotheses we had created at the beginning of the unit. The whole class takes part in this as a group. We talk about how we can get more students to participate in this conversation, a conversation they are likely to find very unfamiliar.

Round 2 of supporting on-going changes in thinking

This is another example of using the core practices called “Supporting on-going changes in student thinking.” This time we work with data collected by others. Several of my novices help their peers in a lesson about working with second-hand data about the Antarctic climate and population fluctuations of key species in the ecosystem over the past 30 years. Making sense of graphical data is really important for all students.

Revising models based on two investigations

My students now revise their initial models, based on two activities—their work with the “energy beans” and the look at second hand data on climate and populations. I press students to think about why they are making changes and ask them about evidence. for their changes. We use scaffolding to guide their revision work.

Argumentation—scaffolding it with specialized tools and routines

This is the beginning of the last core set of practices called “Pressing for evidence-based explanations.” We use a special tool that allows small groups of students to describe claims about the ecosystem they feel are justified, now that they have a good deal of experience with the subject matter. They then identify evidence and the reasoning that links it with the claims. The tool then guides students in getting feedback from their peers, and making changes based on their comments. So, we combine a tool with a routine to help support students’ attempts at scientific argumentation. Its an unnatural way of talking and interacting with peers, so lots of support is needed in terms of scaffolding.

Constructing and deconstructing final models

In the latter part of the “Pressing” set of practices we have students create final models and justify through labeling why they have made key changes since the middle of the unit. We show how you can give students choices about how to draw the final models. In a real unit, taught in high school, you’d also want your students to take what they know, and to apply it to a new event or process—this might follow the practice you see here. I might, for example ask my students the next day to apply what they know of the Antarctic to the changes happening in Yellowstone National Park, where they have a complex ecosystem, but they are also re-introducing wolves. One of the other teachers featured on this website did that with her students.

This site is primarily funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) through Award #1907471 and #1315995

This site is primarily funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) through Award #1907471 and #1315995