How is science done?

Science includes many different cultural knowledge systems and practices people use to understand the world and solve problems. However, Eurocentric knowledge systems and practices have been privileged over others, creating a source of injustice in science and science education. Justice-centered ambitious science teaching stands in contrast to often-observed forms of science teaching that can convey that science gets done only by a few elite people or by following a narrow formula of simplified science procedures . A justice-oriented approach to science teaching fosters science learning by integrating diverse questions, voices, approaches, and resources of historically marginalized people/students to construct an inclusive classroom. With an expansive view of the discipline and how scientific knowledge has been and could be constructed, educators can reshape a new science that sustains Black, Brown, Indigenous, and People of the Global Majority community cultures and ways of being, creating a pluralistic society. Moreover, we can shift perceptions of how science has traditionally been done by helping students see themselves as active participants in science and society and not as people learning settled science (or known facts). Here are more tools and resources to explore:

Dr. Luehmann, Justice- centered AST Framework

NGS Navigators Justice‐centered science pedagogy with Dr. Morales-Doyle

Working Towards Justice-Centered, Multilingual Science and Literacy Pedagogies

What counts as science?

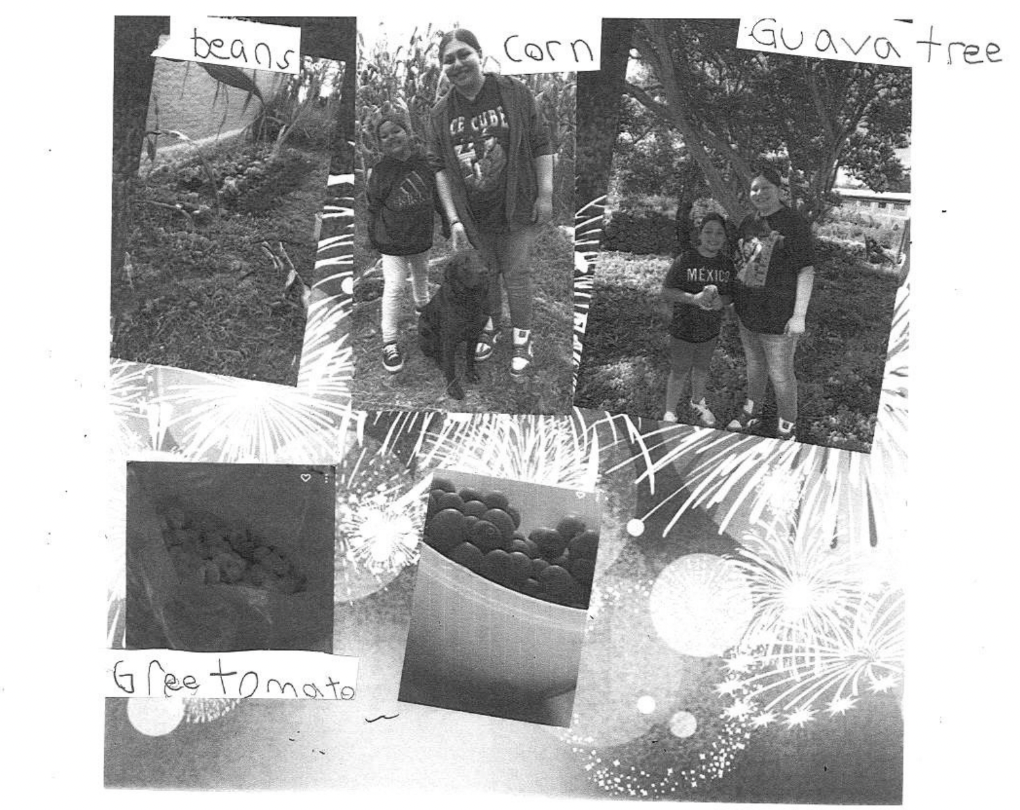

Science knowledge and practice are often presented as acultural and apolitical accomplishments built without connection to people, histories, or power. For example, students learn and practice mechanical scientific processes without placing those scientific ideas and practices in any local, cultural, political, or historical context that matters to them. This approach must include an opportunity to build on the scientific community-based knowledge students bring to the classroom. Connecting students with real phenomena, learning how science communities make sense of phenomena, and how communities are affected by science can provide powerful pedagogical starting points and critical moments of science learning. To support you in planning units of instruction that contextualize phenomena and empower minoritized students and communities, we suggest starting with these tools and resources.

Dr. Kang, Promoting Justice and Equity

Toward Justice-Centered Phenomenon

Tips for Designing Model Scaffolds

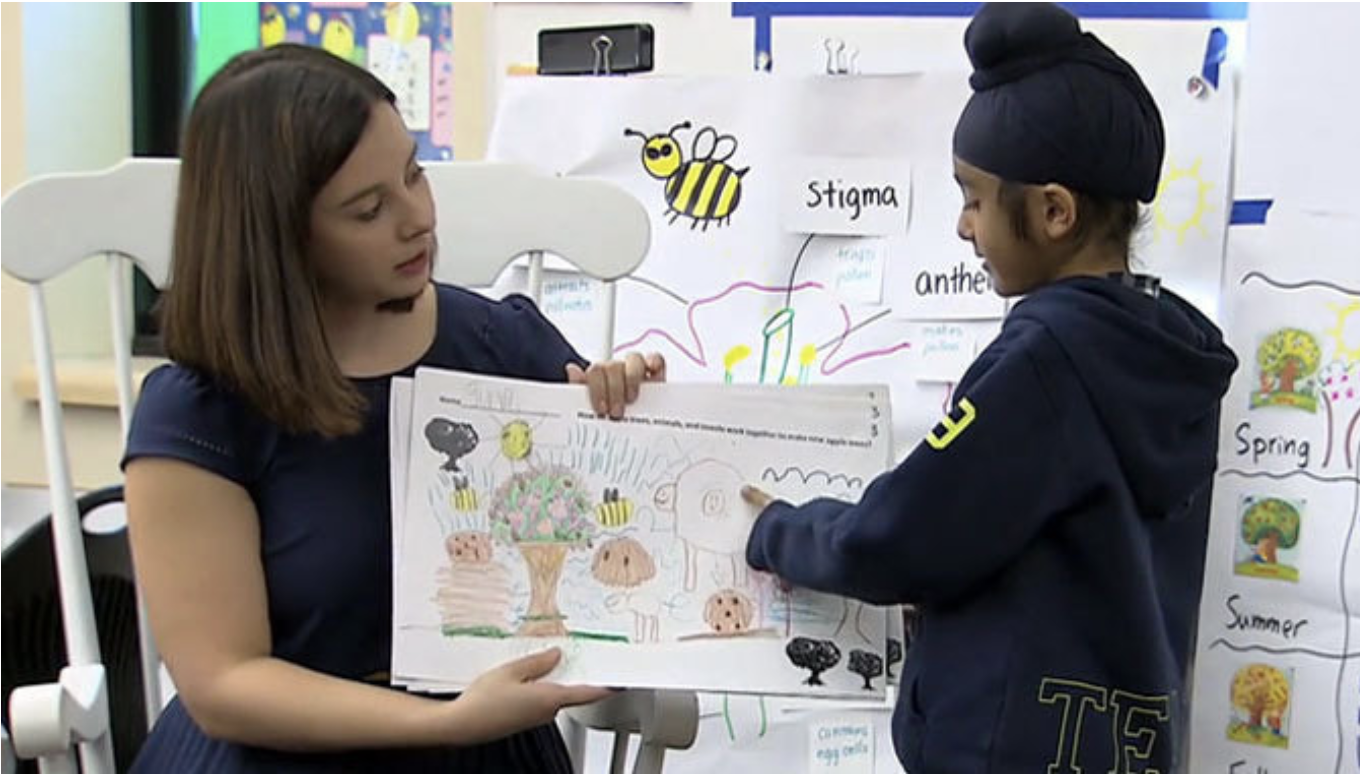

Who gets to do science?

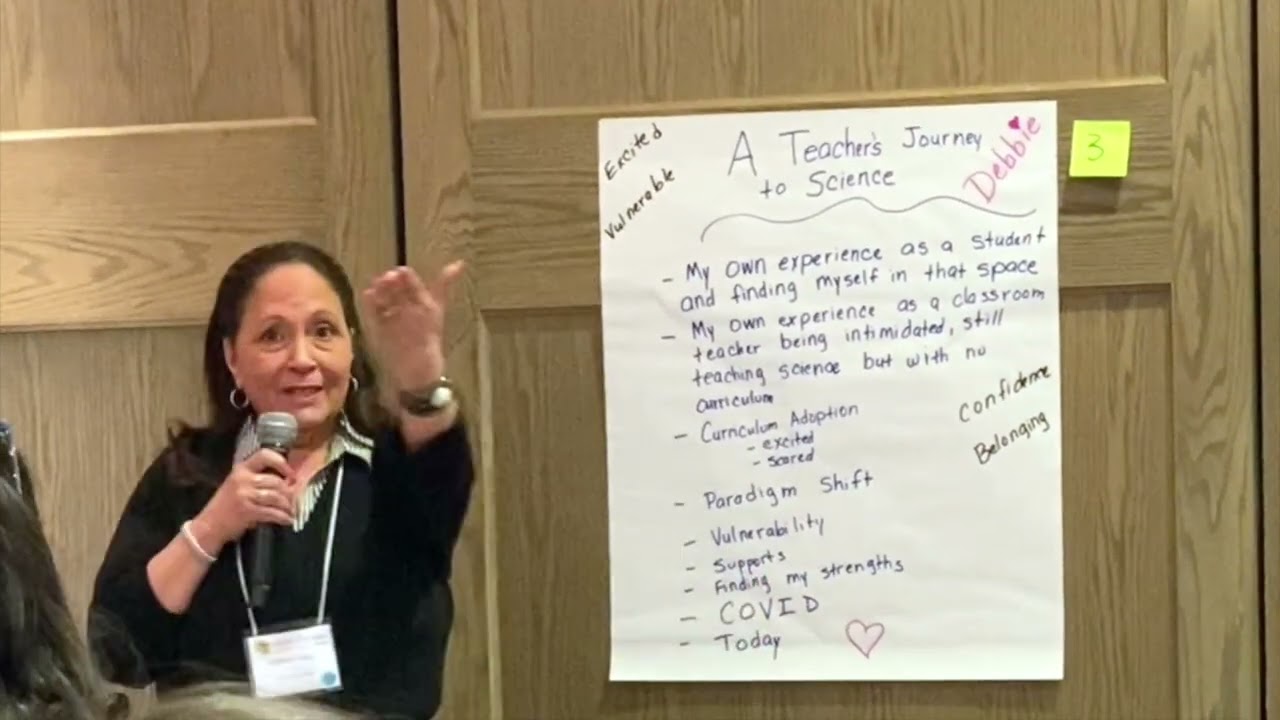

Certainly, everybody can do science, but not everyone gets to do science. The past and present reality of school and society has typically limited science to only a few select people. Furthermore, science done by and for people outside of this select group of people has not been uplifted by mainstream academic science and school systems. This lack of representation of science done by and for members of Black, Indigenous, and Global Majority communities has prevented all of us from learning from science accomplishments and perspectives that provide hope and possibility. To sustain communities excluded from and marginalized by mainstream science, justice-centered science teaching must dismantle barriers that continue to gatekeep participation in science, bring untold stories of scientific work from the margins into the center, address past and present harms of science and school, and then build more expansive and welcoming science learning communities. Justice-centered science learning communities pay close attention to students’ ideas, experiences, struggles, and hopes. Here are more tools and resources to explore:

Building on Students’ Funds of Knowledge

Dr. Calabrese Barton & Dr. Tan, Working toward Rightful Presence

Debbie Diaz, SPS District Science Specialist

We recommend exploring these questions with colleagues and constantly revisiting them throughout the school year. Another way to build a critical equity perspective is to learn from frameworks.

This site is primarily funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) through Award #1907471 and #1315995

This site is primarily funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) through Award #1907471 and #1315995