In my work with PASTEL (Promoting Asset-based Science Teaching for Emergent Language Learners), I wanted to make home-school connection assignments more meaningful. In my experience with district-purchased curricula, home-school connections are usually a bit of a throwaway. Often, they are a letter to send home to the family about what the unit is about. Sometimes, there are questions parents can ask their students to try and get more information from the student about what they are learning. Occasionally, they include investigations to do together as a family, or they might recommend books to get from the library.

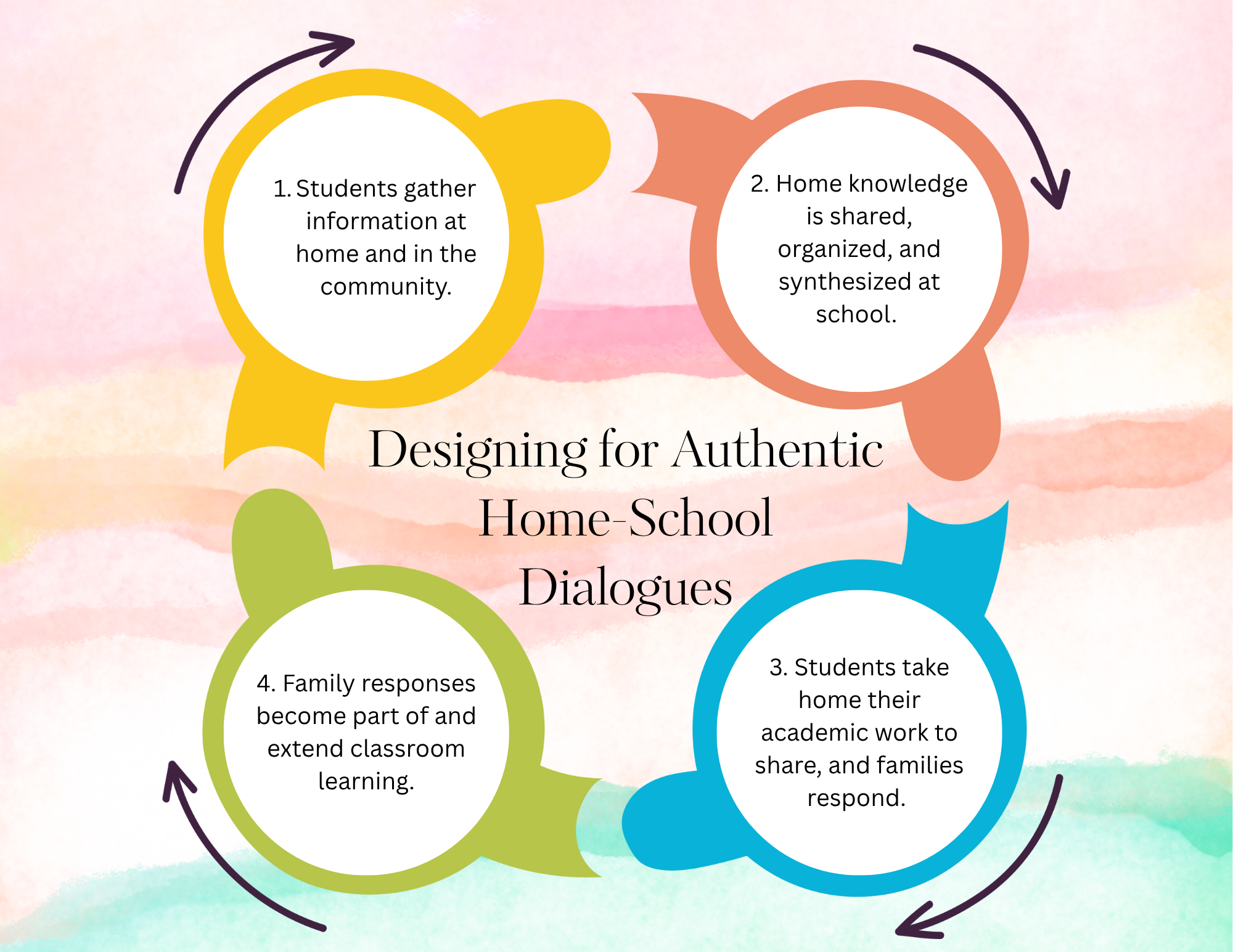

I wanted to change home-school connections from being throwaways, or one-way communications from school to home, into a meaningful dialogue between home and school. I wanted to reshape home-school connections to include more ways of knowing and reposition families as having deep, valuable knowledge about the world that has a central role in our scientific investigations. My students should see the connections between our science classroom, their adults at home, and the scientific knowledge and skills we all possess.

CREATING AND USING HOME-SCHOOL CONNECTIONS IN AN EARTH SCIENCE UNIT.

The science curriculum we used is based around puzzling phenomena. The unit questions students are trying to answer are how or why questions. The hope is that by working through the unit and coming up with an explanation for the puzzling phenomenon, students’ understanding of the larger world will also broaden and they will feel like they understand something about the world they didn’t before. This is one of the joys of teaching science for me. Being there to help facilitate students’ making meaning through their curiosity, exploration, and analysis.

Our unit of study is an Earth and planetary science unit. Students are learning about the movement of the Earth and the position of the Earth, the sun, the moon, and stars in space shape our experience. In this unit, students are trying to figure out what constellation could have been on the missing piece of a mystery artifact that students are told was made about 1,000 years ago.

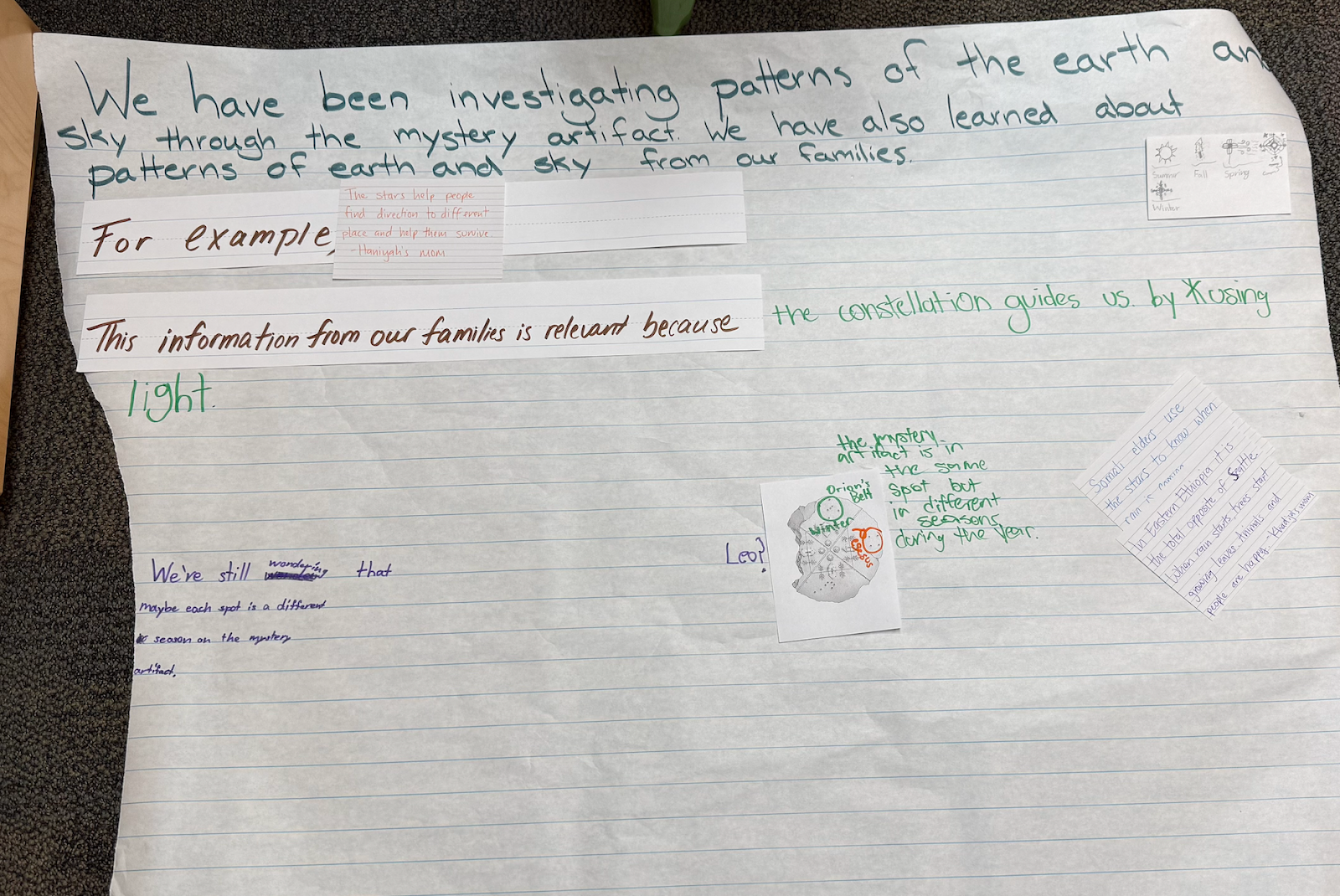

Throughout the unit, the curriculum focuses primarily on students explaining what the mystery artifact might represent, but not why it was made, how it might have been used, and why it was preserved. We agreed that for something over 1,000 years old to have been preserved, it must have been made with care and valued by the community that made it. This was a missing piece in the unit that I knew family connections and familial and cultural knowledge could help enrich and deepen our understanding in our classroom, and help students share back to their families the importance of these connections in our classroom.

In planning the family interview questions, I wanted to give students questions to elicit personal memories and cultural knowledge about how humans everywhere, for a very long time, have made use of stars. This long history is part of the unit itself; the puzzling phenomenon is about decoding a “mystery object” that is more than 1,000 years old. I didn’t want my students to think that connection to stars and storytelling about space is only something ancient or elite; I wanted them to have the opportunity to connect directly.

The first questions I sent home were as follows:

- What did you think or feel about the stars and space when you were a kid? What do you remember?

- How do you feel when you look at the sky at night now? What do you wonder?

- Have you ever been somewhere where you could see A LOT of stars at night? What was it like?

- Have you ever heard about people in the past using stars to help time? Tell me what you’ve heard about.

When I got back the first responses, I realized that the memories and knowledge families shared gave the learning we did so much more context and meaning. Students got back stories from their families about when their parents or grandparents were children and where they lived, and what they saw in the sky. Students also got stories from their home culture, like great uncles who used the night sky for navigating as fishermen, or longstanding knowledge of looking to the sky to plan for when to plant or harvest. The information students brought in from their families was touchstones and real-world knowledge and experience that students were already familiar with. It elevated their understanding right away. Sometimes these connections help to directly position the experience of a beloved family member as integral to understanding an aspect of the phenomenon.

One of the first major concepts for students to grasp in the unit is why stars are not visible in daytime. To build this understanding, we talk about and look at examples of light pollution. Many of my students’ families shared memories of living in places that were more rural and being able to see so many stars at night (question 3 in the first family connection). One family shared, “The sky in Vietnam in the summer has few clouds and you can see a lot of twinkling stars in the dark sky.” Another parent said, “Light from the city illuminates so you can barely see stars, making it feel like I’m not home [in the Philippines].” In class, we rightly positioned this as scientific knowledge that we could refer back to during investigations and class discussions about how the proximity of the sun prevents us from seeing other stars during daytime.

This site is primarily funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) through Award #1907471 and #1315995

This site is primarily funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) through Award #1907471 and #1315995