Case Study: Supporting multilingual learners through translanguaging around models

By Ryann Patrick-Stuart, Caitlin G Fine, Patricia E Venegas-Weber and Erin M Furtak

Our district serves an elementary student population of about 50% multilingual learners, representing over 163 languages. Like many schools in the US, we have had a 10% increase in newcomers in the past year, from countries such as Venezuela, Rwanda, and Afghanistan, totaling more than 3,000 students. While no two newcomers have the same story or experience in an educational system, this increase in our population has created an opportunity to think about how we better support students to make sense of science in meaningful ways who are at English language proficiency levels 1 and 2 on the WIDA Access assessment.

District-wide Professional Development Overview

We were fortunate to have 4 professional learning days this year where teachers engaged in district-wide PD around a focus on supporting multilingual learners in the content areas. These sessions were planned and co-facilitated by a content specialist and a member of our Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Education (CLDE) team. We also had the opportunity to present similar information to school leaders. Our goal was to ensure that, consistent with the CLDE team’s vision, students’ multilingualism is positioned as an asset to their learning, and they have opportunities to grow their English language proficiency in content lessons, such as science.

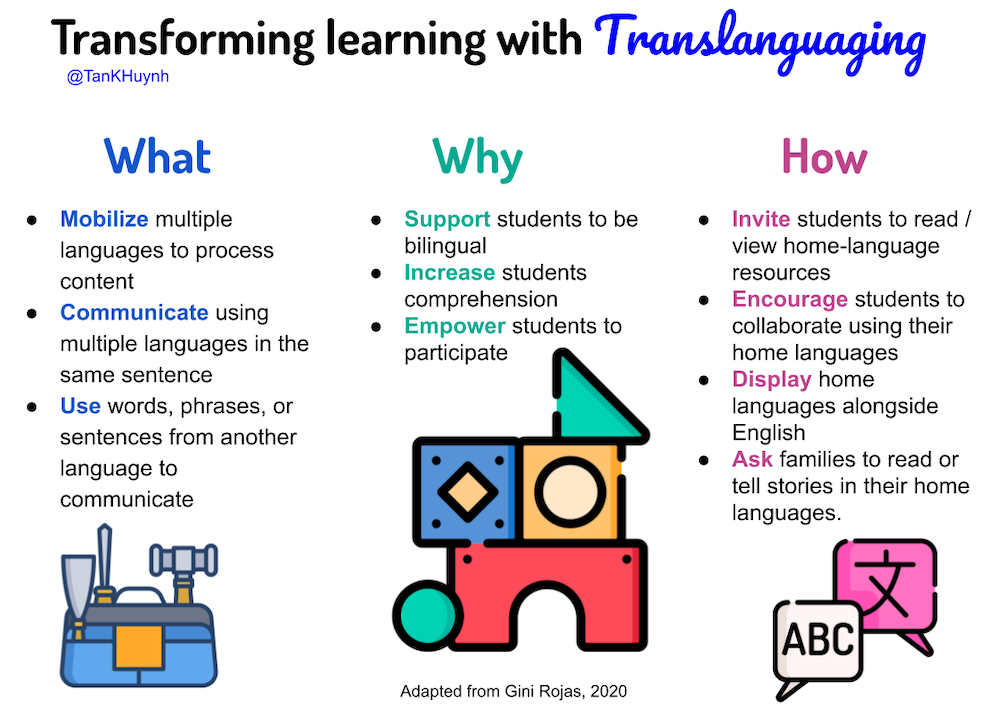

Translanguaging is one specific strategy our district team leveraged (see Figure 1). Translanguaging refers to “the deployment of a speaker’s full linguistic repertoire without regard for watchful adherence to the socially and politically defined boundaries of named (and usually national and state) languages” (Otheguy et al., 2015, p. 281); in other words, inviting students’ to leverage all their linguistic resources as they learn, rather than being limited to English. We used resources from WIDA and TRANSLANGUAGING: A CUNY-NYSIEB GUIDE FOR EDUCATORS along with other tools to talk about how we can use a student’s home language to support learning in our classrooms.

Figure 1. How the district defines translanguaging

| TRANSLANGUAGING

Imagine coming across a group of multilingual youth in an everyday setting. As they interact, you might hear a mixture of languages – for example, Spanish, English – as they describe their lives and the world around them.

Bi/multilingual learners naturally draw upon all of their linguistic resources both in and outside of school settings. Limiting them to speak only in English limits their ability to draw on their multiple languages to engage with and make sense of scientific phenomena.

“Translanguaging has been described as the dynamic communicative norm of (bi)multilingual communities where speakers use multiple linguistic resources for meaning-making that might not adhere to the socially constructed boundaries between languages (García & Wei, 2014)” in Fine, 2022, p. 192.

As a discipline that helps us all wonder about and make sense of the natural world, science is fortunate that, regardless of language or home country, students likely have prior experiences with the big science ideas therefore we have an opportunity to leverage translanguaging so that all can share and utilize their background knowledge regardless of being able to communicate their thinking in English.

AST tools and dialogue strategies are an ideal setting in which to support EB/ML learners. Visual tools such as models can help students to represent their ideas (e.g. Cowie et al., 2011) even when they do not speak a common language. For example, a student described the trends in a potential/kinetic energy graph at the board in Spanish, gesturing with his hand, as his teacher responded and supported him in English (Furtak, 2023).

Additional Discourse Tools:

|

We use an anchored inquiry model from NGSS Storylines that leverages the three main elements of the AST. We anchor our units in a phenomenon or design challenge to elicit students’ ideas. Then we do investigations to support sensemaking and finally, we put the pieces together and press for a scientific explanation. We also understand the power of translanguaging as a science team and how it positions students’ multiple languages as assets or benefits their learning, but we were wondering how we can leverage translanguaging throughout this entire process. As we reflected on our practice overall in science we noticed that students are typically grouped by tables, where they sit throughout the lesson and unit. These groups were typically heterogeneous groups that wereorganized around behavior. We realized that to support multilingual students, this grouping was not always supportive. So we started to think through how we can use grouping and regrouping of students based on home language and ACCESS language level across the three AST elements in our unit: eliciting, sensemaking, and pressing for explanations. This is important so that all students, regardless of their linguistic backgrounds, can actively and fully participate in the inquiry process as they make sense of natural phenomena.

Eliciting Student Ideas

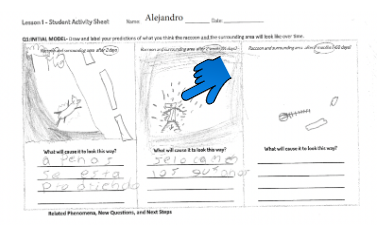

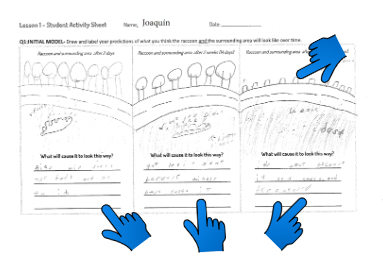

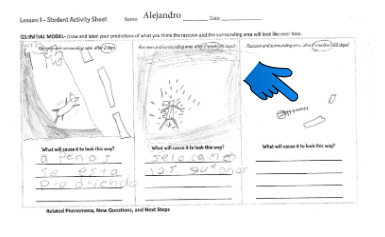

One 5th-grade teacher worked on trying to incorporate translanguaging strategies in the anchoring/eliciting part of the inquiry process to see if we could learn more about what all of the students were bringing to the unit and not just her native English learners. Students were working on the NGSS Storylines unit, “Why do dead things seem to disappear over time?” (Standard 5-LS1-1, 5 -LS2-1).

To support multilingual learners in sharing their ideas on the task, the teacher translated key lesson components into Spanish; in the case of this lesson, this included a few critical words for students to engage with the task. In addition, the teacher adjusted the lesson slide deck so that the prompts asking students to wonder about a dead raccoon on the side of the road and how it would change after 2 days, 2 weeks, and 2 months were written in both English and Spanish. This adjustment helped Spanish-speaking newcomer students discuss their ideas with each other and understand what the task was asking them to think about and do.

During this eliciting phase, this teacher gave students some private reasoning time to draw and write what they thought would happen to the raccoon over time. Before our work around translanguage as a district, teachers sometimes encouraged students to write in their preferred language. However, we didn’t always intentionally leverage students’ home languages beyond that. During this unit, the teacher decided to leverage some of the translanguage strategies and use students’ home language more strategically so that students could fully communicate their initial ideas about this phenomenon.

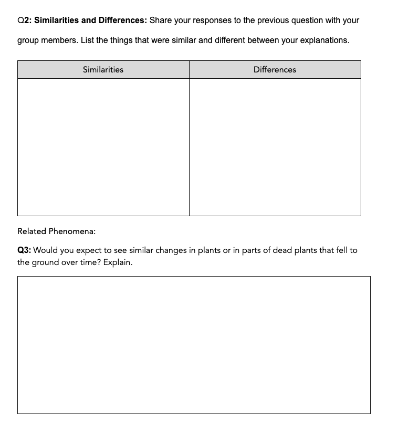

After students had an opportunity to record their initial ideas in drawings and words in their preferred language, she regrouped students to discuss their initial ideas with a partner. The teacher invited students to translanguage as they 1) shared what they had put in their models, 2) compared their models for similarities, and 3) talked through the differences they saw between their models. The teacher grouped students who had at least one common home language so that students could use that language to get their thinking into the room as they elicited and articulated their ideas.

Sensemaking

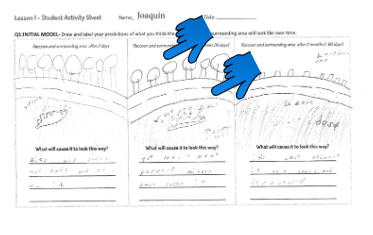

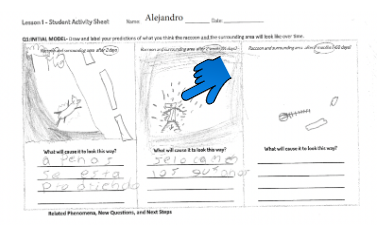

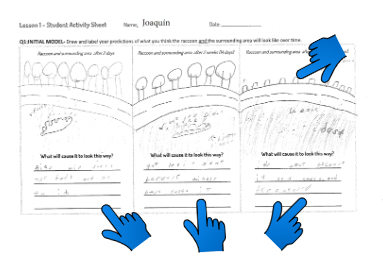

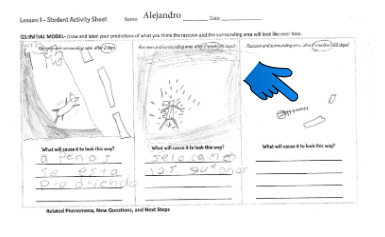

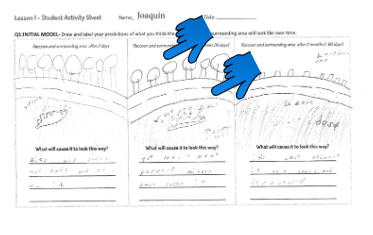

We present the partner conversation between Alejandro and Joaquin (pseudonyms) that transpired as they shared their completed models. Alejandro (ACCESS level 1) and Joaquin (ACCESS level 3) are two Spanish-English bilingual students with different English language proficiency levels. By opening the sensemaking space for translanguaging through the students’ home languages and gestures, and with the support of their models, these students were able to engage in deep sensemaking related to their initial ideas about the raccoon over time. Below, we share the students’ completed worksheets followed by the transcript of their interaction and gestures as they discussed their sensemaking. Once students shared their initial ideas, students returned to their original heterogeneous language lab groups and talked about what confirmed their thinking and what they might change on their initial model.

Completed Student Worksheets

Partner Sensemaking Discussion

| Student Talk |

English Translation |

| Alejandro: No puse carretera porque no vale, haz cuenta que lo movieron.

[pause]

Una diferencia es que no hay, no hay esto [points to trees on Joaquín’s worksheet] y no hay esto [points to the road on Joaquín’s worksheet]. |

Alejandro: I did not put a highway because it does not count, let’s assume they moved it.

[pause]

A difference is that there is not this [points to trees on Joaquín’s worksheet] and there is not this [points to the road on Joaquín’s worksheet]. |

| Student Talk |

English Translation |

| Joaquín: No porque ese es muy chiquito. Una diferencia es que uno tienes la…casi uno tienes la… la raccoon [points to Alejandro’s drawing of a raccoon in the 2 week section] y yo tengo todo _(inaudible)__. Ponlo allí. |

Joaquín: No, because it is too small. A difference is that one of them has … it almost has … the raccoon [points to Alejandro’s drawing of a raccoon in the 2 week section] and I do have everything _(inaudible)__. Put it there. |

| Student Talk |

English Translation |

| (Long pause)

[Students write in their notebook in the t-chart for similarities and differences] |

(Long pause)

[Students write in their notebook in the t-chart for similarities and differences] |

| Student Talk |

English Translation |

| Alejandro: ¿Qué pusiste acá tu? [Points to Joaquín’s worksheet]

Joaquín: Yo puse que las árboles ya ya los cortaron.

[Points to his worksheet drawing of the raccoon after 2 months.] Y la oso ya, ya no está ahí. Se ha ido. Ya no está allí. [Moves his arms back and forth across all the time frames in the worksheet.] |

Alejandro: What did you put here? [Points to Joaquín’s worksheet]

Joaquín: I put that the trees were already cut. [Points to his worksheet drawing of the raccoon after 2 months.] And the bear is not there, it is gone. It is not there anymore. [Moves his arms back and forth across all the time frames in the worksheet.]

|

| Student Talk |

English Translation |

| Alejandro: Yo no terminé esto [points to the 2 month drawing], pero lo que lo que puede saber es que está el cuerpo ahí _(inaudible)_ ya toda la como lo esto…la [points to his neck and moves his hand down his neck, as if showing the vertebrae of the raccoon]

Joaquín: La skeleton?

Alejandro: Yeah. Está todo tirado [points to his 2 month drawing] porque lo lo esto [points to the raccoon bones in his 2 month drawing] se va desaporar solo. [Moves his fingers from closed to opened] Por el tiempo. Entonces no, no se lo puede…[audio cuts out] |

Alejandro: I did not finish it, [points to the 2 month drawing], but what you could know is that the body is there. _(inaudible)_ everything like this [[points to his neck and moves his hand down his neck, as if showing the vertebrae of the raccoon]

Joaquín: The skeleton?

Alejandro: Yes. Everything is lying down [points to his 2 month drawing] because it is [points to the raccoon bones in his 2 month drawing] going to decompose alone. [Moves his fingers from closed to opened) Because of the time. So, it can not…[audio cuts out] |

This story highlights how districts can incorporate translanguaging and multimodal representations (such as drawings and gestures) in the eliciting or anchoring part of an inquiry model.

Supports that teachers can integrate to support their multilingual and newcomer students with AST tools include:

- Grouping students purposefully and regrouping through a lesson (heterogeneous language groups, by similar home languages, by similar ACCESS language level)

- Strategically translating key terms to support sensemaking

- Inviting students to translanguage in small group and whole group interactions

- Incorporating opportunities for students to draw models to represent their science thinking

While this was a valuable first step, we realized in our district that we have more to learn and, as always, more questions we are curious about. To ensure that translanguaging practices don’t stop there, our district unit planning process needs to change. We are now wondering what we need to add and change in our unit planning process to ensure that we continue translanguaging throughout the entire inquiry process. Additionally, in this classroom, there was another student who was also at ACCESS Level 1 on the WIDA ACCESS assessment, however, their home language was Arabic and we did not have another student who spoke Arabic to pair him up with for small-group and partner conversations. We are now curious how to leverage these strategies when there are multiple home languages in the class, but maybe not other students who share those languages.

This site is primarily funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) through Award #1907471 and #1315995

This site is primarily funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) through Award #1907471 and #1315995